Today, March 8, 2021, marks the 110th anniversary of International Women’s Day, a day to celebrate all the wonderful accomplishments women have made within politics, health care, science, education, the creative arts, and more. Had it not been for the 15,000 women who marched on the streets of New York City in 1908 advocating for equal rights, this monumental day and the progression made for women’s rights would not exist. A year after this historical day, socialist Clara Zetkin coined the idea of IWD (International Women’s Day) as a way to bring attention, and change the oppression women were facing around the world. She made this proposal at a conference that consisted of 100 women from 17 different countries who all unanimously agreed, and International Women’s Day was first celebrated in 1910 across Europe.

There is a different theme for IWD every year. For 2021, it’s #ChooseTo Challenge which means being self-aware and responsible for all our actions. The purpose of this theme is to be prepared to challenge certain inequalities that are apparent in our society, and eliminate gender biases and norms. Countries around the world have gone through many changes this year given the circumstances of the pandemic. However, a tremendous amount of accomplishments and progressions have still been made by women in 2020 and and 2021, regardless of the restrictions virtual life has come with.

To start off, 2021 began the year with our very first Black, Asian, and woman vice president Kamala Harris. This was a huge victory, and life changing for the future of women in politics and other leadership roles. Some more milestones include the provision of menstrual products being free for all in Scotland! This lifts a huge obstacle faced by many people who menstruate. It helps move closer towards the abolishment of period poverty. Everyone should be able to manage their menstrual cycle in a safe manner, even if they can’t afford the products, which is why this movement is so important.

On top of that, two women Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna both won a Nobel prize in chemistry, which challenges the gender norms of male dominated fields.

Excitingly, Forbes noted that an increasingly high amount of women have been applying for Business programs at the university level in 2020. They also explained how workplaces have become more flexible, due to the uncertainty and change Covid-19 has placed on work schedules and environments. This new way of life is helpful for the working mother, and allows them to raise a child without giving up a career. For those living in “traditional” households where the man works and the woman stays home, these roles may be confronted if the husband switches to online work. Tasks are being balanced out and now we’re seeing couples split up chores rather than having one person do them all.

Regardless of all the wonderful accomplishments made, we need to address the inequalities that women are still facing in the twenty-first century. This day is about choosing to challenge, and by being aware of these injustices, women can better advocate for themselves and others. Below, we’ve listed a few sectors where work still needs to be done, specifically within Canada. Findings are from Canadian Women’s Foundation and Endometriosis Foundation of America.

The way we celebrate IWD will be different this year, but there are still many ways you can commemorate the day regardless of the pandemic. You can do this by supporting women led businesses, and this doesn’t mean having to buy anything! Following them on social media, or promoting their brand on whichever platform you use is a great way to do this. You can also donate to charity organizations dedicated towards the advocacy of diverse women and situations. Other ways of celebrating include watching a film or reading a novel written or directed by a woman. You can also attend a panel discussion that goes into depth on issues such as education and workplace inequalities. If you want to dress up, wear some purple attire as this signifies justice and dignity. We also encourage you to recognize how awesome you and the women around you are. Support each other, spread love from this day forward!

Written by: Taryn Herlich

16 Charity Organizations You Can Donate To In Honor Of Women’s Month

https://www.bustle.com/p/16-charity-organizations-for-women-to-donate-to-in-honor-of-womens-history-month-2019-16767362

12 Inspiring Movies To Watch On International Women’s Day 2021

https://hk.asiatatler.com/life/10-inspiring-movies-to-watch-on-international-womens-day

Resources:

https://www.endofound.org/the-disparities-in-healthcare-for-black-women

https://www.workflowmax.com/blog/10-excellent-ways-to-celebrate-international-womens-day

https://www.forbes.com/sites/elissasangster/2020/12/16/want-to-see-more-women-leading-in-2021-together-we-can-make-it-happen/?sh=7c062f5f3778

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-01-31/women-leaders-are-doing-better-during-the-pandemic

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-56169219

https://www.canadianwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/FactSheet-VAWandDV_Feb_2018-Update.pdf

For women of colour, there’s a gap within the pay gap

Depression is one of the most common forms of mental illness. According to recent research, over 20% of people in the United States have experienced at least one episode of major depressive disorder in their lifetime. With symptoms including sadness, apathy, low energy, and reduced libido, it’s no wonder that depression can take a serious toll on relationships.

All relationships take work. But, when you’re dating someone with depression, even ordinary challenges become magnified. Compound that with the heavy burden of trying to effectively support your partner through their depression, and you can very quickly find yourself feeling completely hopeless. You should never try to fill the role of a therapist, but you can implement strategies, specifically ones recommended by mental health professionals, to provide support while balancing your own needs.

Awareness is power. Understanding the types of symptoms your partner faces will help you have more patience and empathy. You’ll also learn that sad moods and irritability are not always caused by any particular event or action. Learning about depression will also help your partner feel more understood.

When someone we love hurts, it’s common to try and immediately fix it. Instead, ask your partner questions about their needs. Simply asking, “what can I do to help?” creates a meaningful conversation that helps them feel heard and allows them to express what they want. Even if the answer is “I don’t know,” expressing your support and willingness to help offers comfort.

It’s normal to feel frustrated when the emotional burden of depression looms over your relationship. One of the most powerful and helpful tools you can offer your partner is being patient. Patience is especially crucial with difficulties such as low libido. You can’t fix your partner, but you can let them know that they have space to struggle.

Although you have the best intentions and maybe even good advice, it’s not your place to offer advice. Instead, frame your “advice” as encouragement. Avoid using terms like “need” or “should” and focus on encouraging them to engage in helpful activities. Avoid saying: “You need help”, “You need to go outside” or “You should eat healthier.” Instead try framing it like this: “Maybe a long walk outside will make you feel better.”

Depression often causes people to lose interest in doing things they once enjoyed. On difficult days, it can feel like climbing a mountain just to get out of bed. If your partner seems short, distant, irritable, or disinterested– don’t take it personally. The symptoms of depression can often wear people down to the point where they say things they don’t mean or behave in ways that don’t reflect how they truly feel. Remind yourself that this illness zaps away joy and has nothing to do with your role as a partner or their desire to spend time with you.

Sometimes, the best support you can offer is merely being there. You can’t fix it or take away the pain, but you can sit with them as a supportive force while they endure it. It may be uncomfortable at first, especially if your partner is hurting greatly. You don’t need to discuss anything, you don’t need to offer solutions– just be there. You may sit together in silence, hold them while they hurt, or lay together. Your emotional support offers them a feeling of safety and stability.

It’s normal to feel stressed, worn out, or even resentful when your partner is experiencing depression. It is common for partners to lose sight of their own needs, which can bring many negative feelings into relationships. Make sure to prioritize your own self-care by taking time to exercise, decompress, eat right, and reach out for support when you need it. You won’t be much help to your partner when you’ve stretched yourself too thin anyways.

Sometimes, a person with depression will act in a way that’s disruptive to your life. This may mean things like canceling plans or lashing out. Even though you understand that depression is the cause, it can still be hurtful. Create boundaries for yourself where you preserve your own needs while not causing your partner harm. For instance, when your partner cancels plans you were excited about, go ahead and do them anyways. During arguments that turn nasty, you can remove yourself from the situation to de-escalate. Healthy boundaries protect you and your partner from mounting resentment and negativity.

When your partner has negative thoughts and cognitive distortions like “nobody loves me” or “I’m a failure,” it’s normal to want to tell them how silly that sounds. A more helpful approach is to validate your partner’s struggles without agreeing. You can try saying things like, “I know depression makes you feel that way, but I’m here, and I love you,” or “that’s a tough feeling to endure, I am here to support you through that.”

Telling your partner you love them, you’re attracted to them, and that they are special can all feel futile as they experience depression. Even if your partner doesn’t deem receptive, it’s important to still offer them affection. Your “no-strings-attached” affection creates a feeling of safety as they struggle with difficult emotions.

It can be emotionally draining and feel unfair to experience a relationship with depression. Set a timer on your phone each day that reminds you to practice gratitude. During this moment, write down or mentally list one to three things you are grateful for. This act will help you regain perspective and encourage positive thinking– reducing stress and improving happiness.

It’s possible to feel overwhelmed by your partner’s experience with depression. Don’t be afraid to ask for help. You can talk to a trusted friend, support group, or find a professional counselor to help you through your own emotions. Reaching out can help you practice your communication and build your coping skills.

A relationship requires teamwork, and it’s rarely 50/50. When one team member is hurt, the other must sometimes take on more responsibilities to keep things moving. Depression makes it hard to focus, feel motivated, and do daily activities. Similar to if your partner broke their leg, you might need to amp up your contributions as they work through their symptoms of depression. After all, you’ll need their extra support one day too!

Some days, it can be difficult to find compassion. You’re frustrated, overwhelmed, and feel under nurtured. Remind yourself that this person you love is hurting in a profound way. Their actions and behaviors are often due to the chemical imbalances in their brain caused by depression. Think of how hard it must be for them to feel sick and in pain every day, and dig deep to find compassion in those moments.

If your partner is hesitant or lacking the drive to go to therapy or do other healthy activities– offer to do it together. For instance, engaging in online couples and marriage counseling services can be an excellent way for both partners to find external support and learn healthy coping mechanisms, while avoiding the obstacle of convincing your partner to leave home. Similarly, getting your partner motivated to engage in activities like walks and dinners is easier when you go along with them.

If your partner is actively in therapy, they will be given homework assignments and tools for healing. Partners not in treatment may also adopt some self-care habits that help combat depression. Actively participating and even joining your partner in activities like journaling, meditation, and breathing techniques encourages them to engage in healing behaviors. As a bonus, you’ll gain mental health benefits along the way!

Despite the wide prevalence of mental illness, there is still some stigma attached. When discussing depression with your loved one, avoid using terms like “crazy” or “mental” to describe their experience. Depression is a physiological illness that is documented and as real as asthma or diabetes. With that in mind, be delicate when talking about it and refrain from making your partner feel flawed or weak. They are bravely weathering the storm, and they deserve to do so with dignity.

Some days, your partner may not feel like going out. Rather than isolating yourself socially, continue to maintain a social life. It may feel funny to go out without your partner, but socializing is an important activity for support, distraction and revitalization.

If your partner is getting worse and unwilling to participate in activities that contribute to their recovery– you may need to evaluate your relationship. Do your best to encourage them, support them, and offer to accompany them to any appointments. If none of these tactics work, have a direct conversation with your partner about your concerns. In some instances, you may need to reassess whether the relationship is working for both of you.

Many people with depression experience thoughts of suicide. It may not be possible to observe when people experience this internal struggle, but occasionally there are warning signs. If your partner is threatening to hurt themselves or suddenly becomes calm and at peace after a period of extreme sadness– you may want to reach out for professional help. You can also call the emergency mental health hotline by dialling 988 (in the United States).

Depression is draining to everyone involved. When symptoms are difficult, it may feel like it’s going to last forever. Remember that the severity is temporary, and there are many effective forms of treatment available (and many more being discovered). Building effective coping mechanisms with your partner (and on your own) will help you weather the storm. Relationships sometimes require a great deal of nurturing during difficult times. The contributions you make will benefit you both in the future.

Depression robs people of many of the daily joys that we often take for granted. As the symptoms of depression wax and wane, they can create a great deal of stress on a relationship. Doing your best to learn how depression feels, communicating with your partner, and approaching your partner’s struggles with compassion are excellent strategies for managing this challenging disease. You can’t fix your partner’s depression or take away their pain, but you can offer an empathetic ear and emotional support. If you feel overwhelmed or concerned about your partner’s wellbeing, don’t hesitate to reach out for professional help.

Written by: Lisa Batten, PhD, CPT, PN1

In collaboration with E-Counseling.com

Imagine you are the survivor of a horrible car crash. One day, while you’re walking down the street, you hear a car horn followed by a screeching noise. Before you get a chance to look around and figure out what happened, you feel a sudden rush of adrenaline. Fear paralyzes you from head to toe, and your mind fills up with images of the accident in which you were involved not long ago. It may look like you’re overreacting from the outside, but from the inside, everything feels so ‘real’ and overwhelming. And so, you sit there shaking and waiting for something horrible to happen.

For someone with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the world no longer looks like a place worth exploring but rather a minefield where every step presents a risk.

As you can probably imagine, being hypervigilant and ‘on edge’ most of the day is exhausting. In time, and without proper help, you will eventually shut down because you don’t feel like there’s someone who can truly understand what you’re going through.

But part of the reason people who’ve been through traumatic events resort to social isolation is that society often fails to provide what people living with PTSD genuinely need.

And it’s not out of ignorance or ill-intention, not always, but merely a lack of understanding of the difficulties associated with this condition. This manifests in the public services offered to them, the reactions of their loves to their condition, and even in the way those around them communicate with them.

Whether someone is dealing with depression, burnout, or PTSD, telling them to simply “Get over it” will trivialize the severity of their condition and make them feel like they’re not strong enough.

Imagine you are dealing with something so painful that it almost seems unsolvable. At the same time, you keep hearing that it’s nothing and you should get over it. At some point, you begin to feel like you are the problem; you are the one who doesn’t have what it takes to overcome your condition.

A traumatic event can send shockwaves for months (even years) after the initial impact.

It’s like throwing a rock into a pond. Even though the waves are not as ‘loud’ as the initial splash, they’re still strong enough to disturb the surface of the water.

But the worst part is that if you find yourself in a triggering situation, your mind will (emotionally) reenact the trauma, which can be shocking enough to make you avoid specific contexts or experience intense anxiety if you have nowhere to run.

Long story short, people with PTSD are not “just a bit shocked.”

Stop!

Nobody, regardless of the problems they are dealing with, wants to hear unsolicited advice. In fact, there’s a good chance that someone who’s going through a rough patch might have already tried what you’re about to suggest.

For people with PTSD, an empathetic ear or a shoulder to cry on is significantly more valuable than any piece of ‘expert’ advice you might have picked off the Internet.

Just stop at “I’m no expert” because you’re definitely not. All you need to be is the person who can listen and understand.

Once again, we have a perfect example of an invalidating response resulting from a lack of empathy and understanding.

When you’re dealing with something as emotionally draining as PTSD, there’s little energy left for anything else. It’s not that you don’t want to do more; it’s just that every attempt to get past your traumatic experience feels like a herculean task.

Patience is a crucial factor during the recovery process, and just because someone is complaining doesn’t mean they don’t actively work on their problem.

Sometimes, people think that making a problem seem less severe will somehow take the burden off the sufferer’s shoulders, thus speeding recovery.

Although the intention is good, playing down the severity of the problem can backfire horribly. More specifically, you risk becoming yet another person who doesn’t understand the pain and difficulties associated with PTSD.

If you want to provide support to someone who’s been through a traumatic event, don’t evaluate the situation based on your criteria.

Listen, understand, and try to see the pain through his/her eyes.

Comparing one sufferer to another can sometimes be useful as it sheds new light on the situation. The fact that life could have been far worse represents a glimmer of hope that paves the way for a better future.

But this perspective only works when the sufferer has already overcome helplessness and is making real steps towards recovery.

Otherwise, it’s just another trigger for shame and guilt.

This reply screams frustration right off the bat.

It’s the kind of thing that tends to slip out of your mouth when, for some reason, you’re feeling emotionally unavailable, or perhaps you’ve grown tired of hearing the same complaints over and over again.

If you don’t feel emotionally available, perhaps it would be wiser to take a step back for a moment instead of venting your frustration to someone who’s already in a dark place.

People with PTSD make a big fuss about it because the pain and anxiety can be truly unbearable at times.

Just like “Others have it worse,” telling someone with PTSD that they’ll get over it simply because you’ve seen others recovering from the same condition is a faulty comparison.

For starters, one person’s trauma is hardly comparable to another’s. People’s reaction to traumatic events varies depending on their personality, emotional resilience, coping mechanisms, and social support system.

Given that the underlying emotions people with PTSD experience most of the time are fear and anticipatory anxiety, it’s no surprise that rational arguments prove entirely ineffective.

Additionally, telling people that they’re irrational will definitely not make them adopt a rational perspective. It will only deepen their sense of worthlessness and helplessness.

Often, a simple gesture of, “Help me understand why this situation is difficult for you” is far more helpful than saying, “Let’s look at your problem from a rational standpoint.”

Facing your fears or, as experts call it, exposure therapy is one of the most effective strategies in dealing with PTSD and other anxiety disorders.

Current evidence suggests that both intensive prolonged exposure and virtual-reality augmented exposure can help individuals overcome traumatic experiences.

But this process should only take place under the guidance and supervision of a licensed counselor or therapist.

For people with PTSD, facing their fears can be a huge endeavor requiring patience and careful planning.

Given that people living with PTSD avoid contexts that could trigger them or behave ‘strangely’ when confronted with a situation that reminds them of their traumatic experience, it’s easy to label them as sensitive.

But this sensitivity isn’t a feature of their identity but a coping mechanism that shields them from further pain and suffering.

Remember that some of them are battle-hardened veterans who could do things that most of us wouldn’t even have the courage to try.

Telling someone with PTSD to loosen up is like telling someone with depression to smile more often.

The reason why people who’ve been through traumatic events seem uptight is that they shield themselves from anything that might trigger that painful memory.

For them, loosening up means letting their guard down, something for which they might not feel ready yet.

Given that a significant proportion of people who struggle with PTSD are soldiers and war veterans, we can understand why this stereotype has taken root.

But PTSD can result from a wide range of traumatic events. From emotional and sexual abuse, domestic violence, and severe illness to car accidents, the death of a loved one, and natural disasters, any event that shakes you to the core can trigger the onset of PTSD.

The best thing you can do is ask before making any assumptions that could put the other person in an awkward position.

Unfortunately, it’s not that easy for the human mind to leave the past behind, especially when the past holds something that has shaken the very core of your personality.

When something traumatic happens, the brain registers the event to prevent it from happening again. That’s why some memories will stick and remain with us forever.

In short, the past isn’t something that we should forget or put behind, but understand, accept and integrate into our experience.

We know that humans possess a diverse spectrum of emotions, some being pleasant, others less so. But each emotional experience has a purpose and a valuable message that we need to hear.

If we choose to focus on “positive vibes only” (and encourage others to do the same), all we are doing is running away from ourselves.

Unpleasant emotions are part of who we are just as much as pleasant ones are.

Although being close to people who’ve experienced a tragedy may feel ‘heavy’ at times, it’s vital to create a space where they can unburden their soul.

As long as ‘the wound is still fresh,’ trying to change the subject to something less tragic in hopes of lifting their mood will only result in disappointment.

There’s a good chance you’ll make them feel like a burden.

Trauma survivors rarely talk about what they’ve been through, especially immediately after the event. It is usually when people notice changes in their behavior that they begin to share their struggles.

On top of that, it’s challenging to be open about something as painful as sexual abuse or domestic violence. Especially when you know that people might not understand what you’re going through, and the authorities might not always have the power to provide proper assistance.

When you’re having a hard time adjusting to everyday life, fun is the last thing on your mind.

Even if you try to do something to take your mind off the problems you face, there’s always that profound sense of imminent threat that’s keeping you from enjoying a fun activity.

Instead of suggesting something fun, try to create a safe space where they can experience a sense of comfort and calm.

Asking this question is like saying, “You should have been over it by now.”

It’s definitely something you don’t want to say to someone who’s already having a hard time going about his/her daily life.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, it takes 6 to 12 weeks of psychotherapy for someone with PTSD to achieve recovery. But keep in mind this is just a rough estimate.

As an outside observer, it’s easy to see the light at the end of the tunnel. But when you’re dealing with something as debilitating as PTSD, all you can see are miles and miles of tunnel.

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a complicated condition with numerous emotional, psychological, and behavioral factors that affect one’s ability to perceive a better future. So instead of desperately pointing towards the light, try helping those suffering from PTSD navigate through the tunnel until they find their own way out.

For tips on what you should do, check out our article Supporting Someone with PTSD.

Written by Alexander Draghici, MS, LCPC

In collaboration with E-Counseling.com

There is a strong link between sexual violence and eating disorders. After someone experiences a traumatic event, it is common for there to be an emotional response such as anxiety, PTSD, and depression. Finding healthy ways to cope with the effects of sexual violence can be extremely challenging, especially if you don’t have a strong support system. In order to feel fulfilled as a human, ensuring that your safety needs are met is crucial. When someone experiences sexual violence, their safety becomes jeopardized, which is why many survivors develop eating disorders as a subconscious coping mechanism for the trauma they encountered.

Of course, there are also many other factors that can contribute or cause an eating disorder. This includes genetics, environmental factors such as bullying, body shaming and the media, as well as certain mental health disorders like PTSD and body dysmorphia. Sometimes, an eating disorder is a cry for help, a way for those around you to understand that something is seriously wrong. It’s not easy to communicate how you feel with words, and a disorder that can physically show itself can act as a harmful form of expression.

During the pandemic, there has been a major increase in eating disorders. This is because there is so little distraction and people are beginning to hyper-fixate on their bodies, using eating as a way to avoid certain emotions, thoughts and feelings. It’s a distraction that for many is easy to develop. For survivors of sexual violence, it can be extremely difficult to manage the effects of an assault during “normal” times, so you can imagine how challenging it can be during isolation.

As humans, we like to feel control in most aspects of our lives. When someone is sexually violated they experience a loss of control over their bodies, and their safety and security needs are put at risk. Sometimes, an eating disorder subconsciously acts as a way to gain that control back. This is because eating disorders dictate what you eat, how much you eat, as well as your physical appearance. Disorders such as anorexia nervosa are based on restriction, the constant surveillance of the food you consume, and in some cases over-exercising. It can give many people a feeling of power, and satisfaction to have a strong influence on how their body looks and feels, even if it’s dangerous for their physical and mental health.

For many people, food acts as a coping mechanism during times of stress, sadness, guilt and anxiety. Food can be comforting, and bring relief when one experiences negative emotions. Both binge eating disorder and bulimia involve eating large quantities of food, but those with bulimia purge after consumption. The act of binging actually releases dopamine, a chemical in our brain that allows us to feel pleasure and happiness. During an episode of binging, it is similar to a high which is why so many people do it, and oftentimes in secret. It’s a way to release those upsetting feelings, and distract yourself from the realities our minds have been facing. However, when the binging is over the feelings of negativity, and guilt from eating these extreme amounts of food wash over our brains. This is when many individuals are inclined to purge as they feel regretful after that consumption. For sexual violence survivors, binging can be a way to release pleasure chemicals which they may be struggling to feel. It is essentially a temporary switch in emotions.

At VESTA, we understand how scary it can be to reach out for help, but already, reading this article is a great first step. An eating disorder isn’t something you should manage on your own. You deserve to be supported and given the necessary help and resources in order to thrive and heal. Below we have listed free helplines that specialize in eating disorders, and articles that go more into depth. There is also a link to a private, online counseling service that is affordable and easily accessible. Finally, it’s crucial that you speak with your primary care provider, as an eating disorder is not only a psychological issue, but a physical issue as well. They can guide you on getting professional help, and ensure the necessary steps to maintain healthy living.

Written by: Taryn Herlich

National Eating Disorder Information Centre (NEDIC): Toll Free Hotline

https://nedic.ca/contact/

ANAD Eating Disorders Helpline

https://anad.org/get-help/eating-disorders-helpline/

Eating Disorder Facts and Information

https://cmha.ca/mental-health/understanding-mental-illness/eating-disorders

https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-illness-and-addiction-index/eating-disorders

Sources

If you or someone you know is in danger please contact 911 or the hotline below to seek help.

Assaulted Women’s Helpline: https://www.awhl.org/about-us

Services safety plans, referrals to services and immediate counseling run throughout Ontario.

We live in an era of technology which has its many pros and cons. While we can access information at fast rates and connect with family and friends, there is also a harmful side. A common pattern within many domestic violence cases is the use of control through social media and smart devices connected to one’s home. Continuing to hold the power in these relationships is the main goal of the abuser and these forms of technology have made it easier to intimidate survivors. Thankfully, there are many ways you can still protect yourself.

But first, let’s understand what you should look for if you feel a spouse, ex partner or current partner is using technology in an abusive manner. Remember, everyone has their own unique experience and even if not all these ideas resonate with you, the steps to protect yourself can still be beneficial. Sometimes, the signs are discreet while others are more overt.

This information is in no way meant to make you scared. We just want you to understand the signs. The next steps in this article will better teach you how to protect yourself against these types of scenarios. Here are some steps to take in order to keep your privacy safe.

Two factor authentication is an app you can download on your cell phone that will connect with whichever social media sites you want it to. For example, if you want your Facebook account to be better protected, then you can connect it to two factor authentication. Any time a new user tries to log into your account they would have to use the code that’s shown in the two factor authentication app, or texted to your chosen number. This in turn makes it harder for hackers to access your private accounts.

Geo-tracking is a feature on our cellphones that many people are unaware of. This setting collects location data that can tell details about private places one may have visited. When we post a picture on social media, our geo-location can sometimes tag the location of where that photo was taken without us realizing it. Don’t put pictures that update followers on your whereabouts or make your location obvious. This can make it easier for your abuser to know when you’re out, and where you spend your free time. Access your cellphone’s system settings and disable the geo-tracking icon. If you have an iPhone or Android, the links provided below will guide you on how to manage this feature and turn it off.

iPhone: https://support.apple.com/en-ca/HT207092

Android: https://support.google.com/accounts/answer/3467281?hl=en

If you’re a Snapchat user, check the app to ensure your location isn’t being shared with your followers. Disable this feature by clicking the location icon that leads you to the Snapchat world map. The location icon can be found on the bottom left corner, when you open the Snapchat camera, homepage, and conversations. Then access your settings which are located in the top right corner of the map. Once you’re in settings, you will have a feature called “ghost mode” and there you can easily disable others from viewing your location.

Written by: Taryn Herlich

Sources:

Legal Disclaimer:

Our website provides general information that is intended, but not guaranteed, to be correct and up-to-date. The information is not presented as a source of legal advice. You should not rely, for legal advice, on statements or representations made within the website or by any externally referenced Internet sites. If you need legal advice upon which you intend to rely in the course of your legal affairs, consult a competent, independent attorney. Vesta Social Innovation Technologies does not assume any responsibility for actions or non-actions taken by people who have visited this site, and no one shall be entitled to a claim for detrimental reliance on any information provided or expressed.

Valentine’s Day can be difficult for survivors of domestic violence. Our society has marketed this day towards happy, healthy couples and for individuals who have faced abuse, it can make this day feel rather disheartening. Social media is often full of unrealistic presentations of happy couples and this can create feelings of unworthiness, provoking individuals to ponder their own decisions. When Valentine’s Day and abuse come together, the emotions can get complicated.

Moreover, many survivors who do leave an abusive relationship may face what’s known as Stockholm syndrome after abuse. This is essentially when you feel compassion for your abuser and struggle to get over the break-up as you still miss being with them. On Valentine’s Day, it can be extremely easy to fall into a cycle of reminiscing on the positive times you had with this person, because let’s face it, even an abusive relationship can have good days. That’s essentially what keeps survivors holding on. They hope one day this person will change, and focus on the fond memories they may have had at the beginning of the relationship. During a pandemic, it can be especially challenging, as there is little distraction to help dissipate these thoughts and in some cases, triggers.

So, let’s find ways that Valentine’s Day can be a day full of self-love rather than sorrow. This day should be about admiring your inner strength, and celebrating you as a wonderful individual deserving of recognition.

A personal love letter is a great way to reflect on life, and recognize all the qualities that make you special and unique. It’s similar to telling yourself positive affirmations which help re-frame negative self-talk. The more you tell yourself that you are worthy, kind, smart, and a good human being, the more your mind will believe it. One of the first steps to healing is self-love and a love letter to yourself is a great way to begin or continue the process. This article on Glamour has some amazing examples of letters survivors wrote to themselves.

Why not make Valentine’s Day about treating yourself! Relax and do what makes you feel good. Self care can be as small as doing your makeup (something many people actually find therapeutic) to colouring, writing, taking a bath, going for a walk, speaking with your therapist, or even unplugging from social media.

We’re in difficult times as the pandemic is still present. However, if you live with friends or family that you like, try initiating a movie or dinner night, and have a fun day of celebrating the ones you love! This day isn’t only for celebrating romantic relationships. If possible, go on a socially distant outdoor walk with a friend to switch things up.

Baking is another act of self care and for many, is extremely relaxing and a great way to unwind and relieve stress. Not only are you creating something delicious but baking actually allows you to express creativity.

There is no shame in calling a helpline on Valentine’s Day. If you need that extra bit of support right now, you should absolutely reach out and get it. Sometimes having someone who doesn’t know you, listen to your problems can be a great relief.

Remember, it’s okay if you feel certain upsetting emotions on Valentine’s Day. Your feelings are valid, and normal so don’t be too hard on yourself. You’re only human and quite frankly doing the best you can. In fact, just reading this article is such a wonderful step. You are loved, and so worthy.

If you are currently in an abusive relationship, we recognize how challenging this day can be and how it can be even more difficult to leave on the days leading up to it. There is a pressure that Valentine’s Day will solve certain issues, and that with flowers, chocolate, perhaps a necklace, this day can be special and peaceful. We recognize that you may be holding onto those grand gestures, those moments of kindness, and that on this day your heart yearns for some form of love. The pressure of any holiday can make it harder to leave, especially the ones that are based on love. Know that you are worthy of kindness and respect. This is not your fault, you are not alone, and you are appreciated and loved. Please, seek support by involving a trusted family member or friend, and contact a hotline that can help guide you in leaving (we will have them listed below). If you’re in immediate danger call 911.

Resource Link For Helplines In Canada

https://www.dawncanada.net/issues/crisis-hotlines/

Sources:

https://www.allure.com/story/valentines-day-guide-for-domestic-violence-survivors

Written by: Taryn Herlich

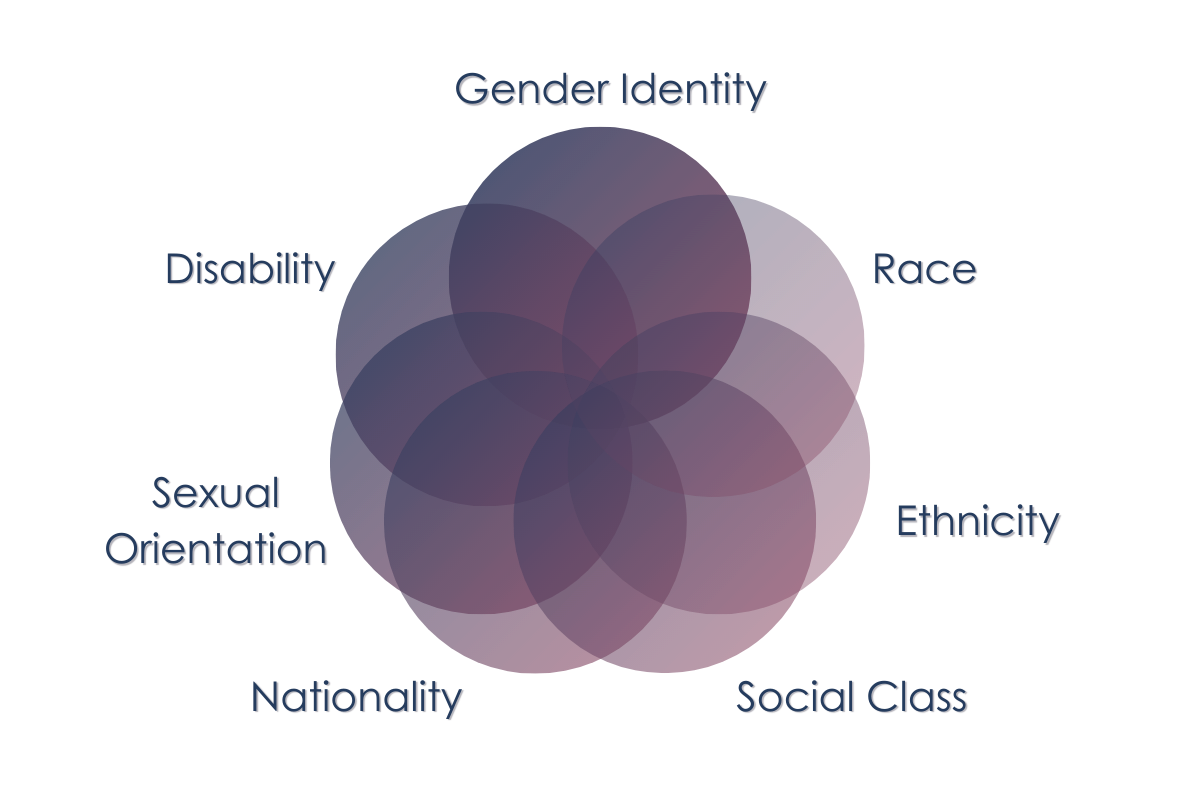

There is no doubt that the #MeToo movement has transformed the culture beneath the laws of sexual violence. This online phenomenon has provided many women with an accessible outlet to share their personal experiences regarding sexual assault and violence. Not only has this unified women’s voices but has revealed crucial information about the nature of violence against women. While it is true that women all around the world experience sexual violence, it is critical to understand that not all women are equally likely to experience violence at the same rates. BIPOC communities experience greater rates of violence and challenges unique to their own circumstances. This is where it becomes important to take an intersectional approach in understanding how violence differs for women across various communities. Intersectionality essentially highlights “how interactions between different aspects of a person’s identity and social location, including age, race, ethnicity, can leave some people more vulnerable to experiencing sexual violence than others”. This lens offers a thorough understanding of why Indigenous women experience higher rates of violence in comparison to other groups of women.

Indigenous women are three times more likely to experience assault than non-Indigenous women. Among non-spousal violent incidents, 76% were not reported to police. Shocked? Surprised? You should be. Historical trauma caused by residential schools continues to diminish the perspectives of Indigenous women. Government officials making problematic remarks regarding the status of Indigenous women and sexually exploiting them has also contributed to their vulnerabilities of higher rates of sexual violence. So, you might ask, why don’t they just go to the police? Isn’t that a simple solution? Sadly, that may be a last resort for some of these women. Some Indigenous communities have tense relationships with law enforcement, including police officers which make reporting crimes of sexual violence difficult . The lack of support and fear of being shamed also prevents them from speaking to authorities. Moreover, since most sexual violence experienced by Indigenous women tends to be committed by individuals from non-Indigenous communities, these women fear they won’t be heard or worse, have their experiences undermined by these officers.

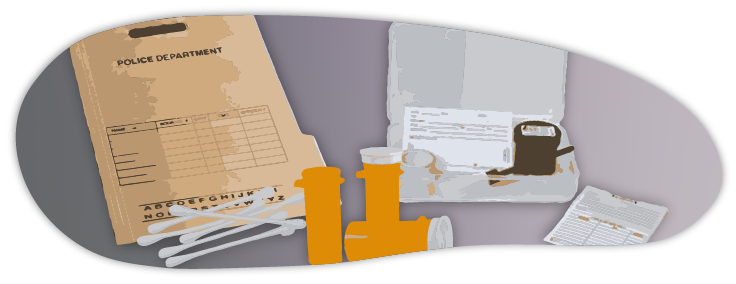

Sexual violence against Indigenous women is essentially positioned at the crossroad of sexual discrimination and racism. An additional roadblock they experience is the lack of federal funding and support provided on reserves, making the reporting process far more difficult and inaccessible. There are fewer resources for them to utilize including, sexual assault forensic tests. The DNA that is received from these tests is crucial to catching the individual committing the crime. However, some of the women may not even have the chance to use this kit if no one is able to provide this resource to them. Police training and education is crucial to ensure rates of violence decrease for these communities. On top of that, unheard voices need to be heard and validated.

We have come a long way. Feminists and feminism are smashing the patriarchy and breaking glass ceilings. However, our work is not yet done. There are still substantial differences across lack of reporting of ethnic groups in sexual assault cases and we must be vigilant to address these issues and redirect federally funded resources to increase accessibility.

Sources:

Written by: Shreeya Devnani

Legal Disclaimer:

Our website provides general information that is intended, but not guaranteed, to be correct and up-to-date. The information is not presented as a source of legal advice. You should not rely, for legal advice, on statements or representations made within the website or by any externally referenced Internet sites. If you need legal advice upon which you intend to rely in the course of your legal affairs, consult a competent, independent attorney. Vesta Social Innovation Technologies does not assume any responsibility for actions or non-actions taken by people who have visited this site, and no one shall be entitled to a claim for detrimental reliance on any information provided or expressed.

A forensic exam kit also known as a rape kit, or sexual assault evidence kit – is a thorough medical examination conducted to collect and document physical evidence after sexual assault. DNA evidence from a crime like sexual assault can be collected from the crime scene, but it can also be collected from your body, clothes, and other personal belongings. This kit is used for investigative purposes by the police, and the use of this kit is entirely up to your discretion. As part of this exam, the following samples may be collected:

Along with this, photographs of injuries, and clothing articles are also collected and stored as evidence. These samples are important to record evidence of assault, and potentially uncover the assailant’s DNA. Prior to this exam, a medical examination is conducted to treat injuries, and prevent pregnancy and STIs. This is often a difficult experience, and you are welcome to stop the process at any moment. Your comfort and consent at each step are the key to moving forward during the examination.

You are given a choice to have the collected evidence stored for a limited period of time or sent to the police. If you decide to pursue legal action, examination centers offer assistance in contacting the police and filing a report. In the case that you are unsure about reporting, evidence collected will be frozen, and stored at the center for up to one year*.

The length of the exam may take a few hours, but the actual time will vary based on several different factors.

As a part of this exam, you are encouraged to prepare yourself and know what to expect when you walk in.

If you are considering having a forensic exam done, here are some things that you can do to ensure that evidence is protected. If possible, do not

Remember to bring an extra pair of clothing, as clothing from the assault may be collected. The best evidence can be collected up to 72 hours after the assault. The earlier the visit, the more evidence that can be collected and the sooner that injuries, or STIs, and pregnancy prevention can be administered. However, you can still come in after the 72 hours to get a kit administered.

This is undeniably a difficult experience. To make it easier to navigate, bring along someone you trust. Some assault crisis centers will send someone to accompany you to the examination if you wish, often called an advocate. Be aware that if you invite someone other than an advocate into the exam room, they could be called as a witness if you decide to report the crime.

Here are steps from RAINN of what to expect during a sexual assault forensic exam:

*The time frame of one year is accurate in Ontario, Canada as of the published date. We encourage you to check your local regulations as it varies by jurisdiction.

Sources:

https://www.sadvtreatmentcentres.ca/assets/resource_library/members_only/OHA_Guidelines.pdf

Sexual Assault Evidence Kit (SAEK)

https://www.rainn.org/articles/rape-kit

Legal Disclaimer:

Our website provides general information that is intended, but not guaranteed, to be correct and up-to-date. The information is not presented as a source of legal advice. You should not rely, for legal advice, on statements or representations made within the website or by any externally referenced Internet sites. If you need legal advice upon which you intend to rely in the course of your legal affairs, consult a competent, independent attorney. Vesta Social Innovation Technologies does not assume any responsibility for actions or non-actions taken by people who have visited this site, and no one shall be entitled to a claim for detrimental reliance on any information provided or expressed.

The Covid-19 lockdown has created new struggles for those dealing with mental health issues. For survivors of sexual violence, repressed feelings and memories may resurface during this time, due to the little distraction and social contact. Oftentimes, it can become very easy to ruminate on past events when there’s a lack of other subjects to think about and again minimal distraction and social contact. With certain resources such as counselling no longer being in person, and financial aid being scarce for many, it can be challenging to find the help you need. Feelings of anxiety, depression and OCD have been far more prevalent during the pandemic, and those with existing mental health issues report them worsening. If you’ve felt as though your mental health is struggling, you are not alone. During this time the most important thing to do is to look after yourself by implementing self care daily. There are also many wonderful toll-free hotlines if you need someone to talk to. We have listed them at the end of this article.

For now, let’s dive into how you can manage your mental health during these uncertain times.

Having a routine to distract and keep yourself busy is a great step. I don’t expect you to be insanely productive, just set up small tasks such as making dinner, reading twenty pages of that new book, jogging for fifteen minutes, etc…

While social media has it’s pros, there can also be many negative messages and triggers conveyed through certain platforms. If you notice that your social media is creating upsetting feelings, or triggering traumatic memories, limit or delete the app. For example, many individuals share their story of sexual violence on social media. While this is extremely brave and lowers the stigma, it could also be a major trigger bringing up unwanted flashbacks, memories and negative feelings for you.

It’s important to stay connected to friends and family during this time. Whether it’s a quick call or socially distanced walk, maintaining some form of human interaction is beneficial. It’s a great distraction and break from things that may create stress within your life.

I know this is often an overused tip but when you exercise you do release endorphins that make you happier. You will feel great afterwards and certain feelings of sadness, depression, anxiety or worry may decrease.

Many survivors of sexual violence develop or have symptoms of PTSD which can cause an overactive amygdala. This can in turn create more feelings of panic, fear and anxiety. Colouring actually helps calm the amygdala, which in turn reduces fear, panic and anxiety. It lessens the reaction of certain triggers and ultimately proves to be a very relaxing and therapeutic activity many survivors partake in. Click here to read more about emotional trauma and brain damage and click here to read about how the brain is affected during trauma

You are human and should do what you feel you’re capable of. Don’t put too much pressure on yourself to feel productive everyday. It’s okay take a break, relax and recognize when you may be reaching burn out. You absolutely deserve to take time for yourself.

Sit back and watch an episode of your favorite show, do the things that make you feel happy. Right now, you are going through a situation that isn’t normal for anyone’s mental health. You are doing your best in a scary time, while also managing your own trauma and that deserves recognition!

Written by: Taryn Herlich

When a spouse, partner, sibling, or other loved one has been raped or sexually assaulted, it can generate painful emotions and take a heavy toll on your relationship. You may feel angry and frustrated, be desperate for your relationship to return to how it was before the assault, or even want to retaliate against your loved one’s attacker. But it’s your patience, understanding, and support that your loved one needs now, not more displays of aggression or violence. These are some tips for when you are helping someone recover from rape or sexual trauma:

Let your loved one know that you still love them and reassure them that the assault was not their fault. Nothing they did or didn’t do could make them culpable in any way.

Allow your loved one to open up at their own pace. Some victims of sexual assault find it very difficult to talk about what happened, others may need to talk about the assault over and over again. This can make you feel alternately frustrated or uncomfortable. But don’t try to force your loved one to open up or urge them to stop rehashing the past. Instead, let them know that you’re there to listen whenever they want to talk. If hearing about your loved one’s assault brings you discomfort, talking to another person can help put things in perspective.

Encourage your loved one to seek help, but don’t pressure them. Following the trauma of a rape or sexual assault, many people feel totally disempowered. You can help your loved one to regain a sense of control by not pushing or cajoling. Encourage them to reach out for help, but let them make the final decision. Take cues from your loved one as to how you can best provide support.

Show empathy and caution about physical intimacy. It’s common for someone who’s been sexually assaulted to shy away from physical touch, but at the same time it’s important they don’t feel those closest to them are emotionally withdrawing or that they’ve somehow been “tarnished” by the attack. As well as expressing affection verbally, seek permission to hold or touch your loved one. In the case of a spouse or sexual partner, understand your loved one will likely need time to regain a sense of control over their life and body before desiring sexual intimacy.

Take care of yourself. The more calm, relaxed, and focused you are, the better you’ll be able to help your loved one. Manage your own stress and reach out to others for support.

Be patient. Healing from the trauma of rape or sexual assault takes time. Flashbacks, nightmares, debilitating fear, and other symptom of PTSD can persist long after any physical injuries have healed. To learn more, read Helping Someone with PTSD.

Avoid judgment. It can be difficult to watch a survivor struggle with the effects of sexual assault for an extended period of time. Avoid phrases that suggest they’re taking too long to recover such as, “You’ve been acting like this for a while now,” or “How much longer will you feel this way?”

Check in periodically. The event may have happened a long time ago, but that doesn’t mean the pain is gone. Check in with the survivor to remind them you still care about their well-being and believe their story.

Know your resources. You’re a strong supporter, but that doesn’t mean you’re equipped to manage someone else’s health. Become familiar with resources you can recommend to a survivor, such as the National Sexual Assault Hotline 800.656.HOPE (4673) and online.rainn.org,

It’s often helpful to contact your local sexual assault service provider for advice on medical care and laws surrounding sexual assault. If the survivor seeks medical attention or plans to report, offer to be there. Your presence can offer the support they need.

If someone you care about is considering suicide, learn the warning signs, and offer help and support. For more information about suicide prevention please visit the Crisis Services Canada or call 1.833.456.4566 any time

Encourage them to practice good self-care during this difficult time.

“I believe you. / It took a lot of courage to tell me about this.” It can be extremely difficult for survivors to come forward and share their story. They may feel ashamed, concerned that they won’t be believed, or worried they’ll be blamed. Leave any “why” questions or investigations to the experts—your job is to support this person. Be careful not to interpret calmness as a sign that the event did not occur—everyone responds to traumatic events differently. The best thing you can do is to believe them.

“It’s not your fault. / You didn’t do anything to deserve this.” Survivors may blame themselves, especially if they know the perpetrator personally. Remind the survivor, maybe even more than once, that they are not to blame.

“You are not alone. / I care about you and am here to listen or help in any way I can.” Let the survivor know that you are there for them and willing to listen to their story if they are comfortable sharing it. Assess if there are people in their life they feel comfortable going to, and remind them that there are service providers who will be able to support them as they heal from the experience.

“I’m sorry this happened. / This shouldn’t have happened to you.” Acknowledge that the experience has affected their life. Phrases like “This must be really tough for you,” and, “I’m so glad you are sharing this with me,” help to communicate empathy.